A young Canadian airman, Ross Bell Nairn, disappeared over Germany in 1944. Evidence of a war crime was uncovered and surreptitiously removed. And then a body mysteriously appeared.

About a year ago, after reading The Job to Be Done by Clint L. Coffey, I found myself going down the proverbial rabbit hole, thanks to a tangential story mentioned in the book.

The story of Pilot Officer Ross Bell Nairn, a young airman from 405 Pathfinder Squadron, could have piqued my interest for the simple fact that he hailed from Science Hill, Ontario, a tiny farming community just outside of St. Mary’s, near my own hometown of Sarnia.

I could also attribute my interest to what I would describe as a soft spot for the stories of those who left this world without descendants and, were it not for serendipity, would have remained largely forgotten.

But there was more to this story that drew me in and wouldn’t let me go: it involves a man stumbling across evidence of a war crime deep in a German forest; the curious removal of said evidence; a certain ambiguity surrounding a tomb in France; and—especially troublesome—a grieving mother and father who went to their graves without knowing the fate of their son.

For several months I researched this story, and was both surprised and frustrated by it. As we approach Remembrance Day, I wish to now share what I learned about the details surrounding this mysterious case, as well as insight into the emotional life of a young Canadian airman in service and the family he left behind.

The story of Ross Nairn

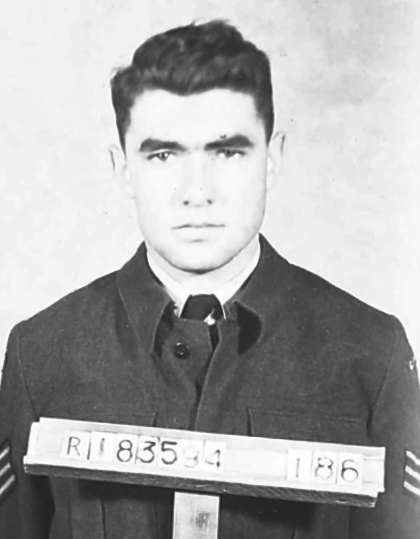

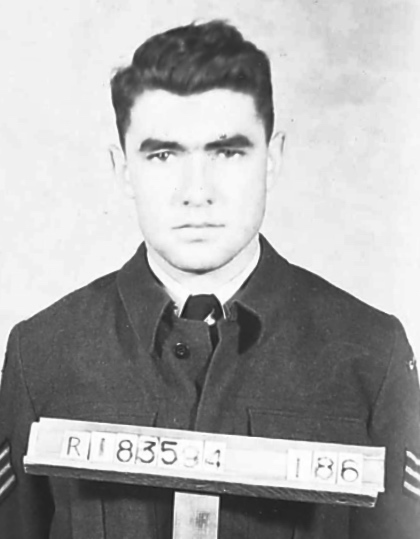

The third of eight children born to William Ellis Nairn and Adella Marguerite Bell, Ross was a handsome young farmer, truck driver, and fur rancher who enjoyed playing sports, hunting, and making model planes. After enlisting in London, Ontario, on August 4, 1942, and going through basic training in Canada, Nairn went overseas. In the UK, he continued training at 24 OTU and 1664 HCU before being posted to 427 Squadron and eventually to 405 Squadron in Group 8, the elite RAF Pathfinder Force, where he earned the Pathfinder Force Badge on May 20, 1944. On August 22, 1944, he received a commission (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., pp. 5–6, 9, 12, 30).

Four days later, on the evening of August 25, 1944, Nairn disappeared from Lancaster PB233, piloted by Flt. Lt. Bill Weicker. The crew, part of 405 Squadron, was headed to Russelsheim, Germany, on a mission to attack the Opel factory there; Nairn was the crew’s air gunner. On the return journey, after being suddenly attacked by a German night fighter, the Lancaster was set on fire and badly damaged. Weicker then put the aircraft into a steep dive, which both extinguished the fire and helped him successfully escape further attack.

After gaining control of the aircraft, however, Weicker discovered that three of his crew members had bailed out without order—in violation of bomber crew procedure—and were missing. Weicker managed to land safely back in England, but with only half his crew.

Coffey writes:

I can’t find it in my heart to be critical of what the three did—they were in a burning, smoke-filled aircraft, diving seemingly out of control, likely thinking they were only seconds from plowing into the ground. For all they knew, their pilot was dead and unable to give the appropriate orders. In those chaotic seconds, the three young airmen made a choice, one they obviously thought was the right one to survive (Coffey, 2023, p. 171).

Eventually, the missing flight engineer (Sgt. Kenneth Arthur Abbs) and wireless operator (Flt. Lt. Henry Donald Brown) would be accounted for: both had been captured on the ground and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp, returning to Canada after the liberation.

Ross Nairn, however, remained unaccounted for.

“He was lying in the fire, with his hands badly burned. I don’t know how I did it but got him on my shoulders and carried him out of it and about 50 yards away.”

-Ross Nairn

Shaking like a leaf

When Nairn bailed out of the Lancaster on that August night, it was not his first time being forced to bail out of an aircraft. While with 427 Squadron, he was on an operational flight to Leipzig on the night of December 3/4, 1943, when an engine on Halifax DK181 caught fire and the pilot was forced to return to England. The crew was ordered to bail out over Suffolk.

Nairn would have a much closer brush with death just a few weeks later when, after an attack on Berlin on the night of January 20/21, 1944, the Halifax bomber he was flying in ran out of fuel over England. The ordeal was best described by Nairn himself in a gut-wrenching letter he penned to his mother on January 30, from the Maple Leaf Club at 111 Cromwell Road in London:

Dear Mother,

It has been the worst week I have ever put in; in my life. I went and saw the wreck in daylight, an awful mess, still don’t know how I got out of it as lucky as I did. We took off about fifteen trees before we hit the ground. I wasn’t even knocked out, except maybe for a few seconds, then I got partly out as it was all burning, before I got right out of it I heard the wireless operator yelling so I went back for him. He was lying in the fire, with his hands badly burned. I don’t know how I did it but got him on my shoulders and carried him out of it and about 50 yards away. The navigator was the only one killed instantly, the rest died since. They nearly all had fractured skulls and broken backs. Most of them would never have walked again. For about three days after I was just shaking like a leaf. In fact I still haven’t gotten over it yet. I have been running all over England to see their relatives and I managed to get to two of their funerals. The bomb aimer died since, that makes four of the crew gone. My left knee and back is still a bit sore. I went to the hospital and saw the wireless operator, he is going to be alright. I didn’t mind being shot up or even having to bail out but when you crash into the ground like that it’s just about enough to put a fellow off flying for life. I haven’t had much sleep in the last week, I think I had better hit the hay now. So long.

Love Ross

(Stevens, 2013, p. IV)

Evidently seriously traumatized, Nairn nevertheless decided just days later that he would fly again. It was arguably more pleasant than ground duties:

I just got back yesterday morning from a funeral, we had another crash here, the whole crew being killed, so me being a spare gunner now they pick on us for jobs like that. Three of us had to go to one of their funerals. Always try to have someone representing the squadron at any funerals (Stevens, 2013, p. 51).

Nairn soon joined Bill Weicker’s crew and was back up in the air. “It sure was nice after not being off the ground for about a month,” he wrote home. (He must have really hated going to funerals.) Over the next few months, Ross would write letters home, describing harrowing scenes of planes going down, as well as the excitement about D-Day:

It was a great sight seeing all the aircraft going out that were taking part in the show, especially the airborne planes with gliders. Also all the ships of all sizes in the Channel. We bombed just before dawn and it was daylight shortly after we left the French coast. Over our drome here there has been a continuous roar of aircraft going over all the time (Stevens, 2013, p. 60).

When the Weicker crew accepted a posting with 405 Pathfinders Squadron, Nairn and his crewmates were transferred to Gransden Lodge near Cambridge, where he remained until he disappeared on the night of August 25/26, 1944.

“I wish to again assure you that when any additional information is received concerning your son, it will be forwarded to you.”

-RCAF

No trace

From Nairn’s service file, we learn that the RCAF drafted a letter to Mr. Nairn on August 26, informing him of his son’s status as missing. On June 11, 1945, following the liberation, Mrs. Nairn penned a letter to the RCAF in Ottawa, offering photographs of her son if it would be of any help in the search for him (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., pp. 55, 70).

A few days later, on June 27, the RCAF Casualty Officer sent a letter to Mr. Nairn, informing him of Flt. Lt. Brown’s witness statement of having bailed out first and therefore not having any information regarding Ross. The Casualty Officer also informed Mr. Nairn that his son would be presumed dead for official purposes, but also that “I wish to again assure you that when any additional information is received concerning your son, it will be forwarded to you” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., pp. 72–73).

Several years later, in September of 1951, the RCAF Casualty Officer sent a new letter to Mr. Nairn, regretting to inform him that, “despite numerous enquiries and a search over a wide area, where your son was reported to have parachuted, no trace of him could be found” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 32).

And there ends the official correspondence between Ottawa and the Nairns concerning their son.

In the dark

Ross was not the first child lost to the Nairns; they had lost a teenaged son in an accident a few years earlier. Mr. Nairn would pass away in 1966, but Mrs. Nairn would lose another one of her children the year after losing her husband, and yet another in 1976. She passed away herself in 1988, followed by the rest of the Nairn children.

Right behind the tragedy of Ross’s demise is the grief of his parents, who were kept in the dark when some very unsettling clues—clues about a suspected war crime concerning their son—came to light after the war.

Over the past year, as I uncovered these details, I have had to ponder whether it was wrong of the RCAF at the time to have withheld these suspicions (Mr. and Mrs. Nairn went to their graves not knowing the fate of their son beyond his bailing out and disappearing without a trace), or whether it was in fact merciful.

By the end of this article, you will be left to ponder the same question, dear reader.

Though he is listed on official memorial sites, any information about a possible war crime involving Ross Nairn is scanty indeed. From what I can tell, it is limited online to a single source, the remarkably well-researched website Aircraft Accidents in Yorkshire; the author, Rich Allenby, writes that Nairn’s “death was probably a war crime and I feel his name deserves to be known because of this.”

Aside from Coffey’s book and Allenby’s website, both of which share what is known from Nairn’s service file (which I will go more into shortly), the only other significant source I could find was an obscure book: Dead men flying: travelling with the lost in Bomber Command, published in 2013 by James R. Stevens (who, sadly, passed away in 2022). The book includes a lot of detail about Ross Nairn (including his personal letters home) and the Nairn family, whom Stevens knew as a child in St. Mary’s. Two of Ross’s younger siblings contributed to Stevens’s book before their passing, and the book confirms that the family were kept in the dark about the suspicions of a war crime (Stevens, 2013, p. 74).

What the service file tells us

The following is a summary of what Ross Nairn’s service file tells us. Anyone today can download it from Library and Archives Canada or Ancestry.com.

The first clue came in September 1945, from a German man named Herr W. Senf, a forester in the city of Homburg, northeast of Saarbrücken. One day when Senf was working in the dense forest outside town on the old grounds of Schloss Karlsberg, an eighteenth-century castle in ruins, he stumbled upon an old crater. The crater—which was very old, part of the castle’s original vaults—could have perhaps served as the perfect spot for Senf to dump loads of branches and foliage from his tree farm; however, when he looked down into the crater, he discovered a parachute harness. He climbed down and lifted the harness to find a body “in a very advanced state of decay and nearly reduced to a skeleton.” Senf added that the body “was lying neatly arranged but uncovered in the crater” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34).

Herr Senf immediately notified the American troops stationed in Homburg, who sent Captain Frederick T. Shroyer of the US Army to investigate. After viewing the body, which still had part of the parachute harness but no identification or signs of anything else, Shroyer contacted the US Army Criminal Investigation Division, who went to investigate for themselves but then left the body there after determining that it was RAF (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34, 43).

An unnamed medical officer (presumably American) was then sent to conduct yet another investigation. Upon examining the body, he discovered a 9 mm bullet hole in the skull, indicating that the airman had been murdered. The record states that “photographs of the skull were also taken,” and that a witness (presumably Herr Senf) remembered the bullet hole being “behind the ear of the deceased man” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34, 43).

But once again, the body was left in the crater—and then it disappeared.

A reporting officer was sent to inspect the crater; by then it was “filled to the top with decaying leaves and rubbish.” Six workmen helped to fully excavate the crater, but no signs of the body were found. A war crime was suspected, and “many people” were interrogated, including Herr Senf. They stated that after the second visit by the Americans, “the body still remained in situ,” and no one “could state definitely that the Americans nor anybody else had removed the body from the crater” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34).

In a casualty enquiry from January 1947, citing “the lack of cooperation of the local residents” of Homburg, it was “suggested that the whole matter be referred to the Judge Advocate General for investigation” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 43).

In June of 1949, 20 MRES (Missing Research and Enquiry Service—which was tasked with tracing and identifying missing personnel from World War II) informed the RAF and RCAF Overseas Headquarters that an investigation had been carried out, report forwarded to the Air Ministry in March of 1947, and then, “at this stage the matter appears to have been dropped” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 36).

A couple of months later, in an August 1949 casualty enquiry regarding Nairn, 20 MRES reported to the Air Ministry that “nobody knows about the result of these investigations” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34).

Whose body?

In that same August 1949 casualty enquiry, however, it is stated that the reporting officer then visited the Homburg police station, as well as the cemetery, hospital, and French Public Safety. According to his findings:

It appears that the body concerned has first been buried in the Heldenfriedhof of HOMBURG. But already next day, French authorities claimed the body and he was exhumed again and brought to the mortuary. From there, he was transferred to the cemetery of the Landeskrankenhaus HOMBURG, and finally interred in Field C, Grave 5. The grave is marked “PIERRE LUGARO” (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34).

Sgt. Pierre Lugaro, an Algerian-born airman with the Free French Air Force 347 Tunisia Squadron, was reported missing from Halifax MZ909 on a daylight raid against Homburg on March 14, 1945. Piloted by Captain Clément Brunet, MZ909 was shot down over Sanddorf, a few short kilometres from Homburg.

According to the French Sureté, the other crew members from MZ909 had already been recovered, and the body thought to be Lugaro’s, though not positively identified, had been buried as Lugaro on circumstantial evidence. Upon request from the British in 1949, French authorities agreed to re-exhume the body in order to compare it to Lugaro’s and Nairn’s dental records (Library & Archives Canada, n.d., p. 34).

And that, according to Nairn’s service file, is where the story ends—until the RCAF’s letter to the Nairns in 1951 informing them that no trace of their son had ever been found.

In Stevens’s book, however, he claims that the body buried as Lugaro on circumstantial evidence was transferred to a cemetery in France in 1950. He cites a report to England stating that “From the evidence available it is probable that the victim was F/Sgt Nairn although in the absence of the body this cannot be definitely established.” Stevens also claims that “British officials backed off their request” for the body to undergo a forensic determination (Stevens, 2013, p. 73–74).

Sadly, Stevens does not provide sources for the above, so I do not know where he got this information from. Presumably, he somehow had access to documents that are not currently in the service file on Library and Archives Canada.

“The man with the pistol may have committed the murder, but there were almost certainly others there who were complicit.”

-Clint L. Coffey

Who lies in tomb number six?

France’s Ministère des Armées states that Pierre Lugaro is buried in tomb number six at the collective gravesite of nécropole nationale Pierrepont in Meurthe-et-Moselle, France.

Assuming the report that Stevens cited was correct, why did the British back off their request to positively identify the body after the French had agreed to it? If Lugaro’s body had indeed been positively identified by forensics, why were the British not informed in order to rule out the suspicion that it could be Nairn’s?

Through my research, I was unable to find answers to these questions. I did come into contact with Gerhard Schmidt of Homburg’s historical society. He had not heard of the story, but kindly conducted a local investigation to see whether it could shed any new light on the mystery. To date, he has not been able to uncover any additional information.

Last moments

In his book, Clint Coffey speculates on the last moments of the airman (presumed to be Nairn) who ended up in the crater:

It is all conjecture, but some conclusions do seem self-evident. Ross Nairn was not killed in a fit of rage by an angry vigilante group—the 9 mm bullet hole was made by a Luger or Walther pistol, the weapon of an officer or Nazi official and not something a local citizen would likely be allowed to possess. Nairn must have been captured (or given himself up) somewhere nearby and then marched a short distance down the forest path to the convenient crater and executed. The man with the pistol may have committed the murder, but there were almost certainly others there who were complicit. Someone had obviously noted the arrival of Captain Shroyer and his team, and word got back to the murderer, who arranged to have Flt. Sgt. Nairn’s pitiful remains moved to thwart any further investigation into the crime (Coffey, 2023, p. 173).

When the RCAF wrote to the Nairns in 1951, informing them that Ross would be commemorated at the Runnymede Memorial, like “many thousands of British aircrew boys, who like your son, do not have a ‘known’ grave,” there was no hint of the years of ambiguity surrounding his case.

As it turned out, however, had the RAF been more forthcoming, the Nairns may have gone to their grave assuming their son had suffered what the French maintain was the fate of another man.

What was Ross Nairn’s fate? Tragically, it seems the answer to that question may be remain irretrievably lost. Wherever his remains are today—whether falsely marked as Pierre Lugaro in France, or forever lost somewhere in Germany—may his sacrifice, and that of the grieving family members he left behind, exit the obscurity of archival files and enter our collective conscious.

Lest we forget.

Sources:

Coffey, C. L. (2023). The Job To Be Done: A Son’s Journey Into The Story Of A WW2 Bomber Command Aircrew. FriesenPress.

Library and Archives Canada. (n.d.). NAIRN, ROSS BELL [File]. https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Home/Record?app=kia&IdNumber=26372&q=

Ross%20Bell%20Nairn&ecopy=44486_273022002859_0331-00179

Stevens, J. R. (2013). Dead men flying: travelling with the lost in Bomber Command. Lake Superior Art Gallery.

Sources for information on Pierre Lugaro, kindly shared by Karl Boucquaert:

- Bourgain, L. (1996). Les bombardiers lourds français 1943–1945: Sarabande nocturne. Éditions Heimdal. (p.205)

- Mémoire des Hommes

- Registre du Révérend Père Meurisse, Aumônier à Elvington

- Relevé généalogique

- SHD Pertes Lourds

Special thanks to the following for their research and input during the writing of this article:

- Clint Coffey

- Lance Fox

- Gerhard Schmidt

- Catherine Hana

- Karl Boucquaert

- Association des Anciens et Amis des Groupes Lourds

Claudia Fox Reppen is a writer and editor interested in exploring the many nuances of complex issues and preserving freedom of expression through the written word. Claudia was born and raised in Ontario, Canada, but has lived in Ringsaker, Norway, since 2002. In 2023, in a transatlantic effort with her brother Lance Fox, she published Following the Echoes: The Quest to Uncover a True Wartime Story of Love, Loss, and Legacy, a poignant story about the search for her British-born Grandma Gladys’s long lost Canadian fiancé, F/O Wendell Pierce Drew, who disappeared over the North Sea in 1944.