I thought that Canada Day would be a fitting day to share this personal story in commemoration of those whom many have called the Greatest Generation. One of the very last of this generation, my paternal grandmother, Gladys Fox (née Hope), passed away recently at the age of ninety-six. (You can read more about her life here.)

Gladys was born in London, England, and grew up in Notting Hill in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in an era when this now posh area was still a humble working-class neighbourhood. The family lived in a flat above the Portland Road Dairy that they owned, and her childhood was a happy and stable one. Everything changed, however, with the events of World War II. As a teenager, she bunked in government shelters and underground stations during the nightly bombing raids of the London Blitz. The death and devastation she witnessed each following morning were a traumatic experience that remained with her for life.

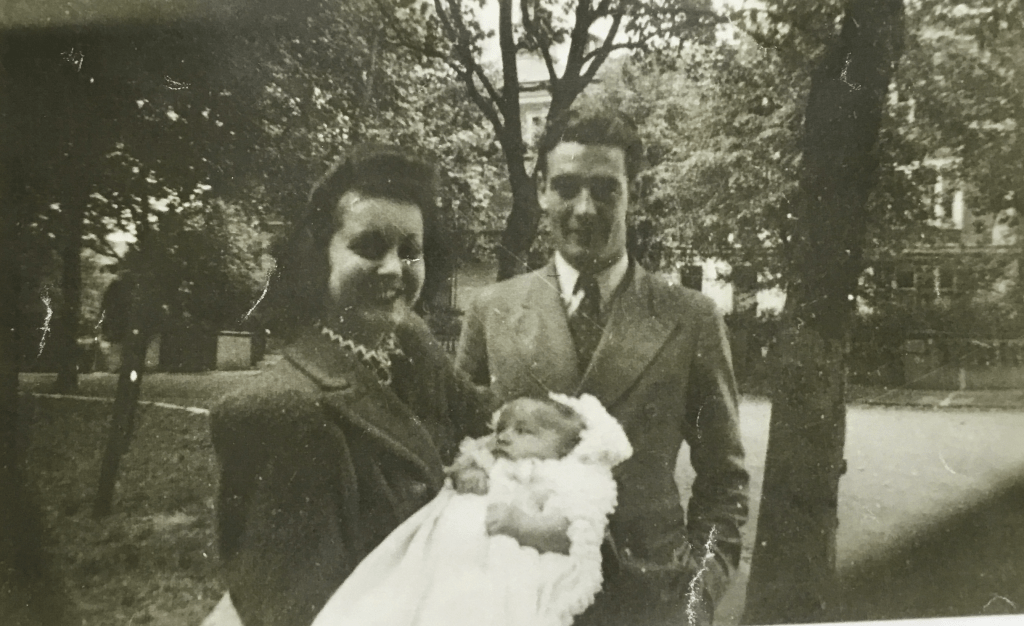

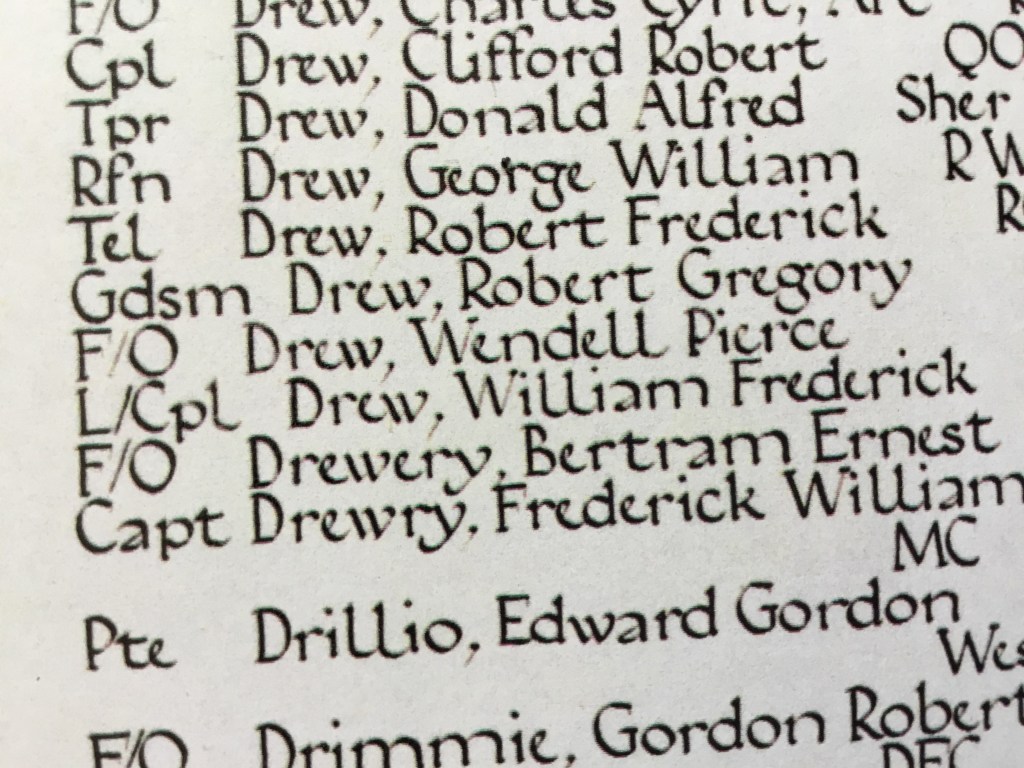

Still, life carried on, and later in the war Gladys enjoyed going to dances. Eventually she met Wendell “Del” Pierce Drew, a young Royal Canadian Air Force flying officer from Radisson, Saskatchewan, and the only child of Albert George and Achsah Ann Drew. Del and Gladys fell in love and planned to marry, but fate had other plans: Del perished, along with his entire crew of seven men, on the night of July 29, 1944, somewhere in the North Sea near Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. His body was never recovered.

An invitation to visit Del’s parents in Radisson brought Gladys to Canada after the war, and ultimately led to her immigrating. Eventually she would meet and marry my grandfather, Charles “Charlie” Fox, in Sarnia, Ontario, where I was born and raised, and where Gladys would spend the rest of her long life.

In the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, the Books of Remembrance display the names of all the Canadians who have given their lives in military service. Every morning at eleven o’clock, a page in each book is turned. In an astounding coincidence on a trip to Ottawa with her daughter in June 1993, Gladys was in the Peace Tower shortly before eleven o’clock on the very morning that the Second World War Book of Remembrance was opened to page 294—the very page displaying the name of Flying Officer Drew. Forty-nine years after Del’s death, my aunt was witness to the profound grief that consumed my grandmother that morning in the Peace Tower.

Gladys got ninety-six years, and everything one can realistically expect or hope for from nearly a century of life: joy, grief, happiness, pain, fear, stability, sorrow, uncertainty, love, and a legacy of family. Del certainly envisioned many of those things for himself, together with Gladys, but at twenty-three it was all over. And even though his name is immortalized in the Book of Remembrance and at the Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, England, I have often thought about Del and the legacy of family that he was robbed of, compounded by the fact that he was an only child and presumably has no living relatives.

I cannot claim to be a believer; I am ambivalent about a life after this one. Still, I cannot help but wish, or imagine—or maybe even believe in a quantum-theoretical, higher-dimension sort of way—that Del and Gladys have been reunited, and that the earthly complexity of the fact that she shared a long life and love with my Grandpa Charlie remain just that: an earthly complexity. I would hope that, as my mother put it, “they’ve found a way to work it all out.”

I am reminded by something the grandfather of a friend of mine once said. Another member of the Greatest Generation and also an RCAF airman, he very narrowly escaped the same fate as Del, and ultimately lived to the age of ninety-five. My friend had learned both German and Japanese as part of his schooling and business travels. One day as they sat together, his grandfather quipped about when my friend was going to learn Italian to complete the whole Axis set. And then he remarked: “But then I guess that’s the world we were fighting for.”

I’ve often thought about my friend’s grandfather’s words these past couple years as I’ve witnessed the growing dysfunction coming from both ends of the political spectrum and the growing breakdown of civil discourse as the cyber world increasingly encroaches upon the real world. I don’t have all the answers to all the problems of the current day, but I know that this isn’t the world that my friend’s grandpa fought for, that Del died for, or that Grandma wanted her descendants to inherit.

This year, with calls to cancel Canada Day in the wake of an unfolding national shame and tragedy that must be reckoned with, the road to reconciliation seems elusive. But I wonder if the road to reconciliation could have seemed any less elusive in the rubble and aftermath of World War II. My grandmother lived through the hardships of the Second World War; her parents had already lived through the First World War, only to have to endure another. Suffice it to say, the British side of my family did not think highly of the Germans. But a few decades after the war, Gladys would be travelling to Germany on holiday (even bringing back a German dress for me to wear as a little girl), and eventually I, her granddaughter, would be enthusiastically learning German and spending time in Germany. It seemed that my friend’s grandfather’s goal had been achieved. And given the multigenerational violent conflicts we see elsewhere in the world, I think that was nothing short of remarkable.

The level of peace, stability, and prosperity that we have enjoyed in the postwar Western world has also been nothing short of remarkable; its longevity and robustness throughout various crises have made it easy to take for granted. Regression seems unfathomable to my generation. But unfathomable doesn’t mean impossible, and recent years have been as turbulent as we’ve seen in a very long time.

Maintaining civil discourse and political stability to the degree that my generation and my parents’ generation have enjoyed is hard work. But there are even harder ways to go about solving conflict, and with much more catastrophic consequences, as Del no doubt could have testified to had he been more fortunate. It seems the greatest battle and the greatest enemy we now face are ourselves, which would have perhaps been unimaginable to Del, even as we have progressed in ways that he would have found equally unimaginable.

I cannot claim to express the thoughts or sentiments of a man I never knew, and who leaves no record behind but a name in the archives, a couple of photos, and a few memories as recounted by my now-departed grandmother. But Del’s legacy is the Canada that I inherited, and I believe it is a legacy worth preserving, even as we must sometimes delve into dark chapters of our history, have difficult conversations, and negotiate tirelessly to reach consensus.

Winston Churchill’s assurance that “We shall never surrender” was what sustained Grandma and her fellow countrymen as they struggled for sheer survival against an enemy from abroad. Could these words sustain us today? To whom shall we never surrender?

In the current state of affairs, I suggest that it must never be to ourselves. In our instinct to avoid shame, we must never surrender to our inclination to evade making amends; in our proclivity for tribalism, we must never surrender to the temptation to sabotage the fragile work of peaceful collaboration and negotiation; and with our limited understanding of the complexities of a well-functioning, stable society (not to mention our fortunate lack of experience with the opposite), we must never surrender to the temptation to dismantle the social institutions that have been the backbone of Western society, providing us with an unparalleled era of postwar progress and prosperity.

I think that my generation’s collective consciousness was profoundly influenced by the experiences of our grandparents, who had lived through terrible times. They were living witnesses, in our homes and in our schools, of events that we always hoped—even expected—they had overcome so we would never have to. Now these living witnesses are, or very soon will be, all gone.

I once heard someone say that most of us are forgotten within three generations. When I think of Del, I think about how he, in all likelihood, did not exist in the consciousness of anyone in the generations beyond his own. And so, with this, I wish to bring his memory into the national consciousness, if even just for today.

Glady would be very proud of you Claudia.

LikeLike

Thanks- this was a very engaging post. I hope his memory continues, and that they somehow are together again.

LikeLike