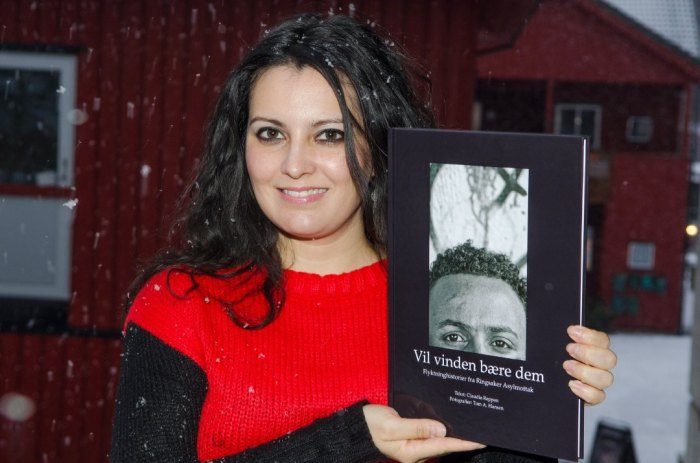

By Claudia Fox Reppen

In February 2010, I first walked through the doors of a place that every Norwegian has heard of, but few have entered: the mottak – short for asylmottak, or “asylum reception centre.” Spread throughout the country, these often run-down, dirty and smelly old buildings decades past their prime serve as the temporary — meaning anywhere from a few months to a few years, and for a handful of extremely unfortunate souls, decades — home to Norway’s asylum seekers.

In between jobs and at the tail end of a bitter breakup with the Mormon religion I was raised in, I was looking for a volunteer endeavour to fill my time — and perhaps also my empty soul. I found both after reading an article in the local newspaper about the mottak in my town. Local citizens were quite good at donating goods but not their time, it said, and so I decided to get in touch with the management.

My first day at “the camp,” as it was also called, I was given a tour and was introduced to several of the approximately 130 residents, some of whom spoke very good English or a bit of Norwegian. They were curious about me, a youngish, dark-haired woman whom they could easily guess was not ethnic Norwegian and therefore assumed to be a new Iranian — perhaps Kurdish — resident or interpreter. When I said that I was from Canada, they wondered what on earth a Canadian was doing at the mottak. When I explained that I was married to a Norwegian and simply a curious visitor, I was received with the warmest of welcomes one could ever hope for. Expecting to spend perhaps an hour or two chatting to people on that first day, I ended up spending eight; while a super friendly woman from Iraq cooked an amazing dinner in the greasy and crowded communal kitchen, a very bright young man from Afghanistan told me his story in the dreary common room that smelled of sweat and stale cigarette smoke. That evening, I encountered what I would encounter many times over in the years to come: incredibly warm and hospitable people eager to share their stories.

In the years that followed, my Canadian late twentieth-century simplistic view of multiculturalism — the fun kind where people ate tasty food, wore colourful clothing, maybe spoke another language at home, but basically all got along — would disintegrate along with my political ideals and faith in Europe’s ability to successfully integrate the influx of refugees and migrants of recent years.

As anyone who has left the Mormon Church or any other authoritarian religion can tell you, a faith transition has a profound effect on your life as you are confronted with evidence that contradicts your most deeply held truths and simultaneously constrained by family and organizational loyalties. The religious apostasy that ensued my eventual encounter with reality was a painful experience. But as life-changing as it was, it is possible that my later encounter with the realities of mass immigration would prove to result in even more profound personal disillusionment.

From approximately 2010-2013, I spent hundreds of hours with asylum seekers from many different countries such as Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Pakistan, and Ethiopia, as well as Palestine. Through extensive personal research, I also learned about the various political and social conflicts that had driven these people from afar to my neck of the Norwegian woods. I quickly became a folkevenn — literally “friend of people” — helping asylum seekers navigate their lives here by translating and guiding, gaining a unique perspective in Norwegian and European asylum policy in practice as I went.

It was often hard to see meaning or consistency in the decisions of the Norwegian immigration authorities, particularly with the rejections that seemed especially harsh. I saw cases of some family members being granted asylum, while others in the same family were to be deported back to Afghanistan; I learned about the horrors in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia through seeing the burn marks of torture on the body of a young man whose plight was evidently unconvincing to Norwegian authorities; I met Assyrian Christians from Mosul who languished for years at the mottak, losing yet another appeal to stay even after the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq. I asked myself, If they don’t qualify for refugee status, who does? Like most of the people I met during those years, they would all eventually be deported or simply disappear, perhaps to try their luck in another European country.

Although I tried in several cases to appeal on behalf of people who had received rejections — going as far as writing op-eds to local and national newspapers, or lobbying politicians at the local as well as national level — I was never successful in getting a single case overturned. Most often, I was simply a listening ear and a bit of a shoulder to cry on. Sometimes I even cried myself.

I tried sharing what I had learned with Norwegians by participating in an NRK-produced P3 radio documentary, as well as by writing a self-published collection of stories about residents from the local mottak. Some showed real interest, and I never met any open negativity, but for the most part people remained politely indifferent. Still, I found my volunteer work enjoyable and meaningful; helping vulnerable people who found themselves in a strange land had become my new “religion” of sorts. And, at the time, it was difficult to imagine ever losing my faith in this religion. But, just as when I had lost my faith in God, reality was once again about to rear its ugly head into another one of my unchallenged world views.

I was treated with great respect and hospitality by virtually everyone I met and was invited to numerous dinners and parties. I recall being the only woman at the table in a room full of Arab men and sharing a fantastic evening of laughter and good conversation. A part of me felt honoured, but as their own women remained in the hallway or in the kitchen, I remembered how I had felt as a young woman in the Mormon Church when I was told to leave a room full of (male only) priesthood holders.

I would again feel conflicted at Afghan celebrations when I saw all the women, girls, and children move to a separate, smaller room while I and several Norwegian women remained where the real celebration took place (i.e., with the men). As Western women, we danced alongside the men, and I probably imagined — though not without some cognitive dissonance — that I was playing a vital role in the successful social integration of these newcomers to Norway. An abrupt ending to that notion came when I danced with some of the Afghan women and my husband thought to take a picture, only to be angrily confronted by one of the men who forced him to delete it. (Not exactly a great starting point for integration into arguably the most gender-equal society on the planet.)

I was troubled by what I perceived to be people taking advantage of the system: Once in possession of a Norwegian passport, some refugees travel back to the country where they were supposedly in grave danger to visit family, get married, or for all we know engage in nefarious activities. Recently it has come to light in Norwegian media that Somali immigrants often send their children to so-called “Quran Schools” back home to (quite literally) beat the Norwegian out of them.

It is also well known that young second-generation Norwegian Muslims, under the watchful eye of the Oslo “morality police,” are under intense pressure not to assimilate, and that the mere rumour of a girl having a relationship with an ethnic Norwegian boy may be enough to elicit violence from family members. While it is not uncommon for the numerous immigrants from countries such as Russia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines to marry ethnic Norwegians, it is a rare occurrence with those from countries (Somalia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, etc.) with little in common except for the common denominator of Islam. This is, I believe, one of the biggest hindrances to integration of Muslims in the West. It is also one that I know all too well myself, coming from an authoritarian, fundamentalist religion where marrying outside the faith can have serious social consequences. But while Islam and Mormonism have many parallels, Mormons rarely face threats of violence for going against the tribe.

The prevalence of fundamentalist attitudes and even extremist sympathies would hit closer to home in three unrelated events. The first one, though not directly related to me, was unsettling when it was revealed on national TV that a Somali man who had lived at the local mottak before my time there was wanted in connection with the Westgate Mall attack in Kenya, as well as other terror activities in Africa. Suddenly, an elderly Norwegian volunteer from the local community was on national news, blissfully unaware in photographs that she was standing next to one of Al-Qaeda’s most dangerous men — a man that those who knew him claim showed no indication of his extremist affiliations.

I also started to have suspicions about another young man from Afghanistan who seemed to be very friendly, only moderately religious, and making a sincere effort to learn Norwegian. After being rejected, and under the threat of deportation, he disappeared. Although I had little direct contact with him after that, I still had him in my list of Facebook friends. One day I noticed he had shared an antisemitic meme on Facebook that I had read was making the rounds on far-right and Islamist networks. This was very disturbing, but not the first time I had encountered such attitudes among asylum seekers. I chose to ignore it, curious to see whether this would become a trend. Soon thereafter, he shared a post glorifying a fallen servant of Allah whom I instantly recognized as being the Canadian ISIS fighter Andre Poulin I had read about on CBC. I cut all ties and was later told by a trustworthy source that this young man had once expressed an intention to target Norwegian forces in Afghanistan if not given asylum. Yet another contact who lived for a time at the mottak later admitted to me that he was aware of several Muslims there who had expressed extremist views.

I stepped out of the mottak for the last time, never to return, the day a well-educated Palestinian friend who had never seemed particularly religious suddenly expressed his unequivocal support for Hamas. When I asked him what he thought of the human rights abuses Hamas inflicted on its own people, he readily dismissed these as rumours, describing Hamas as “educated men” acting “one hundred percent” in accordance with Islam. I was taken aback, as this was one of the last people that I would have expected to sympathize with a group like Hamas not only on a political level, but even on a religious one. (A non-confrontational person by nature, I had rarely discussed politics or religion with asylum seekers; perhaps there was a part of me that knew what I would encounter.) I also genuinely liked this person and knew he was under a great deal of personal stress that could have been a factor in what seemed to me to be a sudden shift. Or was I simply seeing it for the first time? I pondered the implications of this revelation and wondered how he really felt about jihadism, the rights of women, homosexuals, and the inextricability of Islam from every facet of life. While a part of me was curious and wished to query him further, I decided that I did not want to know; I just wanted out. I wished him well and exited the door, perhaps a little quicker than in previous times, with an overpowering desire for distance.

These unsettling experiences were coming on the heels of the revelation that at least one of the stories that I had put my heart and wallet into publishing in order to help local asylum seekers was in fact a complete fabrication. I had suspicions about some of the others as well, and my trust and goodwill had now been eroded beyond repair. I now perceived the roots of extremist sympathies to run deeper and in more unexpected places than I would have previously guessed; further activity there felt untenable and maybe even dangerous. I decided to take a step back and started to devour books, articles, and podcasts about Islam and jihadism — particularly the excellent works of Graeme Wood and Ayaan Hirsi Ali — in order to better understand the ideological roots and motivations behind Islamic extremism, as well as the cultural resistance to integration in the West. The subjugation of women, unquestioned submission to authority, and desire for political influence were all reminiscent of the conservative religious culture in which I grew up — except that Islam was like Mormonism bulked up on steroids.

These unsettling experiences were coming on the heels of the revelation that at least one of the stories that I had put my heart and wallet into publishing in order to help local asylum seekers was in fact a complete fabrication. I had suspicions about some of the others as well, and my trust and goodwill had now been eroded beyond repair. I now perceived the roots of extremist sympathies to run deeper and in more unexpected places than I would have previously guessed; further activity there felt untenable and maybe even dangerous. I decided to take a step back and started to devour books, articles, and podcasts about Islam and jihadism — particularly the excellent works of Graeme Wood and Ayaan Hirsi Ali — in order to better understand the ideological roots and motivations behind Islamic extremism, as well as the cultural resistance to integration in the West. The subjugation of women, unquestioned submission to authority, and desire for political influence were all reminiscent of the conservative religious culture in which I grew up — except that Islam was like Mormonism bulked up on steroids.

It has taken years to process the conflicting emotions of empathy and distrust, goodwill and disillusionment. My goal has been to maintain a balance of remaining compassionate and thoughtful, yet skeptical and pragmatic. And so, it is in that spirit that I share the following hard lessons and what I gleaned from them:

1. When in Rome, do as the Romans — or at the very least, don’t try to burn Rome down

Growing up in Canada, assimilation was the antithesis and nemesis of the “cultural mosaic” that shaped our national pride. This was in contrast to the “melting pot” of the United States, where everyone, we were told, was expected to become “as American as apple pie” — the implication being that we occupied the moral high ground. The need for a certain degree of assimilation, however, is something that I have come to see the wisdom behind living in a small Scandinavian society. We need not be afraid of diversity, but neither do we need to fetishize it to the point of undermining our unity.

Encouraging a certain level of homogeneity of Western culture and liberal values without self-flagellation is important for our political institutions and social cohesion. It is also, I believe, a major factor in the high level of trust that has made the Scandinavian model a success. This cohesion may be slipping away from us through rapid demographic shifts and an accompanying rise in crime and antisocial behaviour which far-right groups conveniently exploit as evidence of a “Muslim invasion,” while those on the left — assuming they even acknowledge problems — attribute to conservative policies of economic inequality.

Anyone who maintains that Europeans want more rapid demographic change is virtue signalling or simply deluded. We may have come a long way, but twenty-first-century Homo sapiens are still biologically programmed through evolution to remember the negative over the positive; we are not ready for a borderless world. We may be the same species, but we do not have a single culture or set of values, and we are under no moral obligation to receive incomers whose values set is at complete odds with our own. When in Rome, a sincere attempt to do as the Romans will be well received by most, but attempts to sabotage or burn it down must not be tolerated.

2. Resettling refugees in Europe may not be ethical to refugees themselves

The Norwegian job market for foreigners is tough, but it can be brutal for a Somali farmer with no education, or an illiterate Afghan woman with several children. While there are many individual success stories, the outcome is often tragically predictable: Despite the best efforts of immigrants and dedicated Norwegian teachers and volunteers, newcomers struggle to make ends meet, often with a large family to provide for in Norway, as well as an extended family back home. Some take up unsecured loans that will keep them in a perpetual financial hole, and it can be difficult to enter a very expensive housing market.

But even as politicians seek to implement policy that will help immigrants succeed, there are ideological barriers; for example, many Muslims who are in a position to buy a home refuse to take up a mortgage because of the ban on interest in Sharia law, putting pressure on Norwegian banks to offer interest-free “Halal loans” available in some European countries. According to the 2016 survey “Islamsk finans i Norge” (Islamic Finance in Norway) by the independent liberal think tank Civita, 88% of Muslims “agree” or “agree completely” with the statement “Regular banks offer loans with interest that is completely forbidden in Islam,” as well as “It is a problem for me that interest-free loans are not available in Norway.” Over 80% “agree” or “agree completely” with the statement “If interest-free loans were available in Norway, I would take advantage of it myself even if it cost more than a loan from a regular bank.”

According to Statistics Norway, as of 2017, 71% of all social assistance payouts in Oslo and 56% nationally go to immigrants, of which 86% are from Africa or Asia. Social assistance payouts to immigrants increased by almost 10% between 2013 and 2017, while the rest of the population saw a decrease during the same time period. The costs directly related to helping refugees get established with housing, language training, and introduction classes are not included in these statistics.

Despite the determination of new immigrants trying to master a new language and make up for lost decades of education, plus the efforts of policy makers and citizens who want to see them succeed, the gap remains extremely wide. Between dismal statistics and personal anecdotal evidence, I question whether it is especially compassionate of Europeans to resettle people where the odds are significantly stacked against them. The economic unsustainability of mass immigration also begs the question of whether it is entirely ethical to take upon us the incredibly costly endeavour of integrating what is in fact a relatively small number of refugees.

In Refuge: Rethinking Refugee Policy in a Changing World, a brilliant book of practical solutions for turning the current dysfunctional system into one that empowers refugees, Paul Collier and Alexander Betts warn us that with around 90% of the world’s refugees remaining in the developing world, “(u)nless policy is properly thought through, the rights exercised by the few can have adverse repercussions for the many.” According to Collier and Betts, for every 135 USD of public money spent on asylum seekers in Europe, one dollar is spent on refugees in the developing world. Also, fewer than 10% of the four million Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan received any material support from the United Nations or its implementing partners.

3. Like it or not, Islam is here to stay — but it needs no protection

In a Norwegian op-ed, Sylo Taraku, a Kosovan-Norwegian former Muslim and author whose professional background includes the Norwegian Organisation for Asylum Seekers (NOAS) as well as The Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI), proposed the following approach to Islam in Europe:

…(w)e cannot distance ourselves from Islam in the West and view it as an undesirable foreign element. Islam is now one of our domestic religions that deserves to be treated in the same way as Christianity — with the same rights of expression, but also the same demands and expectations of adapting to modernity. The good news is that progressive Muslims are at the forefront of the fight against reactionary Islam. This makes matters much easier for liberal Europeans, for then this does not become a conflict between majority and minority, but between progressive and reactionary forces across ethnic and religious backgrounds. When right-wing populists present Islam as a threat, the answer cannot be to portray Islam as a minority religion that needs protection from criticism.

Regressive leftists and Islamists are likely to remain strange bedfellows for the foreseeable future in their attempts to label criticisms of Islamic ideology and culture as “racist” or “Islamophobic,” but there is a rising tide of sensible people who will not be kowtowed into submitting to ludicrous demands of political correctness. Moderate voices — which include liberal and ex-Muslims — cut through the hysteria of the far left and the far right, but tend to get lost in the noise made by these. Surely we can have frank conversations about the incompatibility of elements of Islam with Western European values, and how culture can hinder integration, without portraying all Muslims as a threat or all critics as bigots.

4. Be very skeptical of anyone who does not recognize both sides of this dilemma

The humanitarian catastrophe is such that one would have to be a sociopath to not be affected by the images of traumatized refugees and drowned children. Syrian refugees have dominated the headlines in recent years, but we cannot forget the millions of displaced people from conflicts in Afghanistan, Somalia, Eritrea, Iraq, Yemen, and elsewhere. The suffering is real, the despair heart-wrenching, and the stories compelling.

On the other side, numerous gruesome terror attacks all over Europe, the brazenness of mass sexual assaults committed by immigrants and asylum seekers in Cologne and Stockholm, rising crime in areas that have undergone rapid demographic changes, and the enormous economic cost of settling, educating, and successfully integrating non-Western immigrants on a massive scale are not problems that will solve themselves.

This is an immensely complex issue that should leave you feeling conflicted; if it does not, you have not sufficiently examined the other side. Anyone who calls for a complete sealing of the borders as a solution is as far-removed from reality and lacking in pragmatism as anyone who says that we do not need them at all.

In the end, I believe it all boils down to the following question: should the right of refuge of a foreign national outweigh a nation’s societal, economic, and political self-determination and stability?

While it can seem right to advocate for rights on an individual level, things become more complicated on a larger scale. It is a question that perhaps necessitates an answer grounded in dynamic, pragmatic solutions, as opposed to a “right” answer that is universally applicable to all times and circumstances. But it deserves to be discussed and debated — meaning it deserves to be asked without having one’s sanity or humanity called into question.

In their book, Collier and Betts describe a struggle that occurs between the “heartless head” and the “headless heart,” in which refugees are the losers either way:

The granite bedrock of our discussion has been the inescapable nature of our moral duty towards refugees. In meeting that duty we are obliged to use both the heart and the head. Just as the heartless head is cruel, the headless heart is self-indulgent. The lives of refugees are plunged into nightmare: in responding, we owe them both our compassion and our intelligence.

Because so few people have had the opportunity or desire to interact personally with asylum seekers, there are a lot of heartless heads with strong opinions but completely devoid of compassion. On the other side, the headless hearts working in the trenches with refugees are prone to forgetting the long-term consequences of short-term solutions.

During the first few years of my mottak experience, I was a headless heart, consumed by the suffering and hopelessness, all the while self-indulging in my feel-good role of folkevenn. Only after I became more aware of the scope of the challenges and dangers of mass immigration did I really allow my head to claim its appropriate place.

Whatever the underlying motivations — decolonization, atoning for previous wars and genocides, white guilt, or a genuinely soothing self-indulgence — it is time for Europe to stop undermining itself through its collective headlessness. The status quo is in no one’s interest.

Almost a decade after that first day at the mottak, I am glad that I really had no idea what I was getting myself into on that cold February day. Going in with an open mind and sincere desire to make a difference in the lives of others allowed me to be genuine in all my efforts and interactions. I met many kind and extremely hard-working people, some of whom I hope will remain friends for life.

I also met some people that I hope to never see again. Nevertheless, it was perhaps these people in particular who taught me the most valuable lessons not only about the pitfalls of culture and ideology, but about the less often discussed pitfalls of empathy and the heart.

Recommended Reading and Listening:

- Refuge: Rethinking Refugee Policy in a Changing World — Paul Collier & Alexander Betts

- What ISIS Really Wants — Graeme Wood (in my opinion the best article on the fundamentals of the Islamic State)

- What ISIS Really Wants: The Response — Graeme Wood (follow-up to previous article)

- Why Global Religious Conflict Won’t End — Graeme Wood (about the problem of interpreting religious texts)

- The Way of the Strangers: Encounters With the Islamic State — Graeme Wood (THE book on ISIS, an expansion on Wood’s article from The Atlantic)

- Infidel — Ayaan Hirsi Ali (a pioneer in Islamic criticism at a great personal cost, Ali’s personal story is amazing in many ways)

- Nomad: From Islam to America: A Personal Journey Through the Clash of Civilizations — Ayaan Hirsi Ali

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now — Ayaan Hirsi Ali

- Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue — Sam Harris & Maajid Nawaaz

- The Atheist Muslim: A Journey From Religion to Reason — Ali A. Rizvi (Rizvi is a Pakistani-Canadian physician and author who runs the Secular Jihadist Podcast)

- The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam — Douglas Murray

- The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided By Politics and Religion — Jonathan Haidt

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind — Yuval Noah Harari

- Secular Jihadists Podcast (loads of interesting guests and discussions with people such as Graeme Wood, Sam Harris, Maajid Nawaz, Yasmine Mohammed, and many others whose names you won’t recognize. Also available on iTunes)

“Islam is now one of our domestic religions that deserves to be treated in the same way as Christianity — with the same rights of expression, but also the same demands and expectations of adapting to modernity”.

I see problems here. Hamed Abdel-Samad, son of an imam form Egypt, has written a book about the islamic fascism, where he states that the Quran contains 25 direct commands to kill unbelievers. This is not a 5000 year old Jewish story, but meant for the present. Addiitionally Mohammed is the foremost example for the moslems, and it is impossible to come around that he himslef parttook in voilent acts at a big scale, including killings (no, it was not just selfdefence). So, both the Quran and Mohammed teaches the same thing, and as the Quran is the infallible word of Allah, to the detail, by which moslems may reach Paradise upon minutely following this book, – how can there be harmony with a growing number of followers of this religioin? How can one believe this to be equal with the message of Jesus, not only teaching us to love our enemy, but who also did well to all, and gave himself as saviour of the world? How can one grant rights to a ideologiy which is of the most intolerant kind ever invented?

I believe it is a dangerous error to believe that modernity will change islam, as if this has happend to christianity. If so it will not be islam anymore, as islam is defined by its “sacred books”, and the acts of Muhammed. The Reformation gave access for the lay people, for the first time, to actualley read the Scriptures themselves. They were freed from the roman catholic faith that had corrupted the biblical content to a nightmare. But now all could see that the message of Jesus was salvation through faith, and love from God to carry out to their neighbours. This opened avenues to the enligtenment, and personalites like Issac Newton, studied the Scriptures all his life with the same open mindset by which he penetrated the mysteries of the physical world.

So the change came from the revelation of the content in the Scriptures, not from hiding it, or neglecting it. However, a similar act by the moslems to go back to “their books”, will be a catastrophy, because of the voilence they contain. That will give us RADICAL ISLAM. This is what IS have done, – they believe that the salafs faith, the forefathers success in aquireing “the golden age of islam”, will again surface, by holding to the macabre practices of these descriptions. Several moslems have had to leave islam of pure shame and shock of what they found.

It is wise of you to keep some distance to Resett. Else you will loose your friends, your reputation, maybe your work. That is because of a Resettfobia sweeping over this country. But finally we will have a lawparagraph soon against Resettfobia, Erna Solberg to put all her prestiguous weight into it, and one may possibly in a while have harmonous relations again. So all the Storting says.

I can understand some people may find some comments from this medium a bit over the edge. But on the other hand they are much too soft. For the politicians have allowed a mass emigration which is far from sustainable from any perspective. It is outraguous. So, why does it continue? And finally, why are peolpe upset by Resett, and not the Quran? The major rasjonal antagonism to support, is towards this antihuman manifesto. The moslems deserve our support to criticize it, to the minimum like the Bible for some hundred years, yet this will not happen of fear for the voilence of the moslems. So we loose, surely Europe is finsihed. Thanks Merkel.

LikeLike

A very intelligent and penetrating essay – her aquired insight is impressive.. As to Lesson 3 ,her reflection on Islam’s incompatibility with almost every other faith is clear – what she does not reflect on is the fact that the number of new Muslim migrants arriving far outstrips most Western societies’ internal growth – forcing Islam on societies which are greatly weakened by the widespread agnosticism prevailing i Scandinabia – what to do sabout that?

LikeLike

Wow.

I’m lost for words, actually: This has to be the most clearheaded essay I have ever read on the Norwegian situation.

I have worked in the Norwegian municipal refugee system in close to a decade after finishing a degree in “multi-culti”-studies, and I have, like you, moved on from the “headless heart”-phase. That is not to say I will vote for the Progress Party any day soon, or take out a membership in SIAN.

Anyway, from a disillusioned — yet not quite heartless — Norwegian: Thank you very much for your brilliant text. I have already ordered a copy of Collier and Bett’s book, bookmarked your blog, and looking forward to your future thoughts on the issue.

Again, thank you, and good luck!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have learned a lot from you on this issue. You are right that we cannot be simplistic about immigration, or rely on either a head or a heart. Combining head and heart is what makes us human. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLiked by 1 person